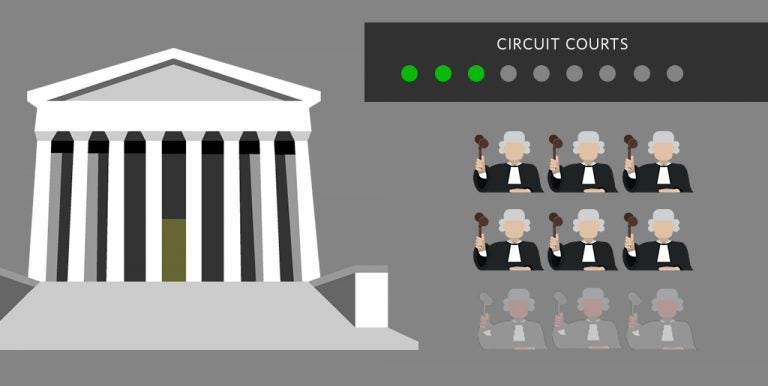

The Judiciary Act of 1789 established a Supreme Court with six justices along with district courts and three circuit courts. Supreme Court justices were required to “ride the circuit”—or travel to different regions and participate on circuit courts. Six Supreme Court justices meant there would be two justices for each of the three circuit courts.

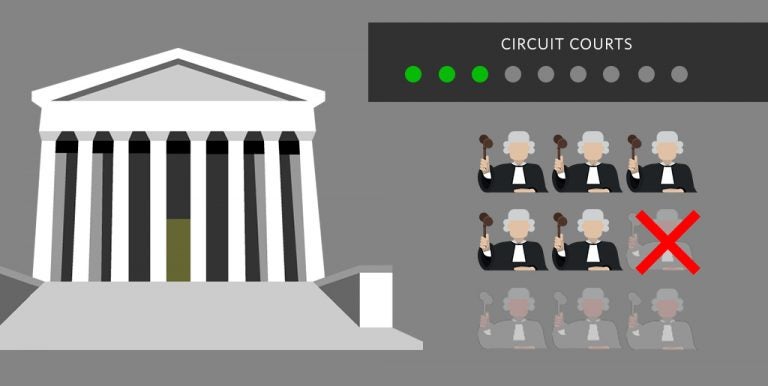

Outgoing President John Adams, a Federalist, signed the Judiciary Act of 1801. It prevented the incoming president (Republican Thomas Jefferson) from appointing a Supreme Court justice, stating that upon the next vacancy, the number of justices would be officially reduced from six to five. The Federalists wanted to prevent their political opponents, Republicans, from influencing the judiciary by nominating new justices (sound familiar?). The scheme didn’t work, since there were no vacancies before Jefferson repealed the act.

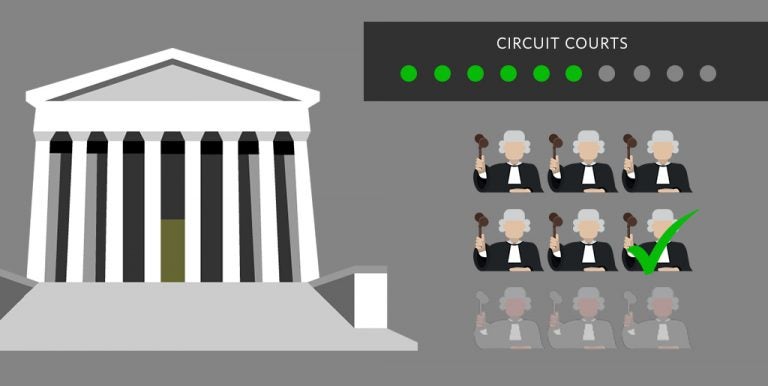

President Thomas Jefferson signed the Judiciary Act of 1802, restoring the official number of Supreme Court justices to six (though the number had never actually dropped to five since there weren’t any vacancies in between the 1801 and 1802 acts.) The number of circuit courts remained at six under Jefferson.

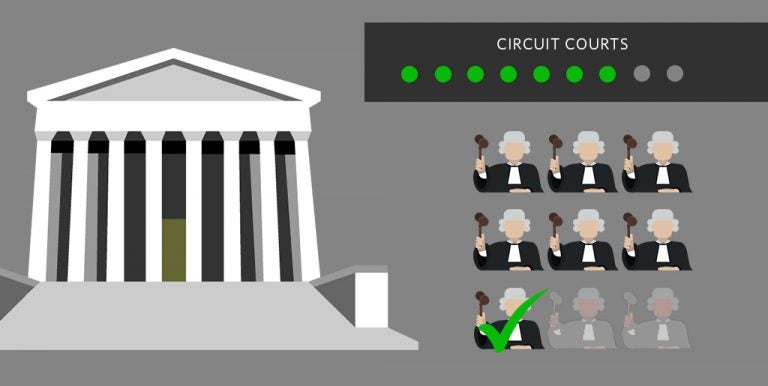

With the addition of new western states, a seventh circuit court was added to the judiciary by President Jefferson. Supreme Court justices were still riding the circuit, with one justice for every circuit. The addition of a seventh circuit provided justification for a seventh Supreme Court justice, appointed by Jefferson.

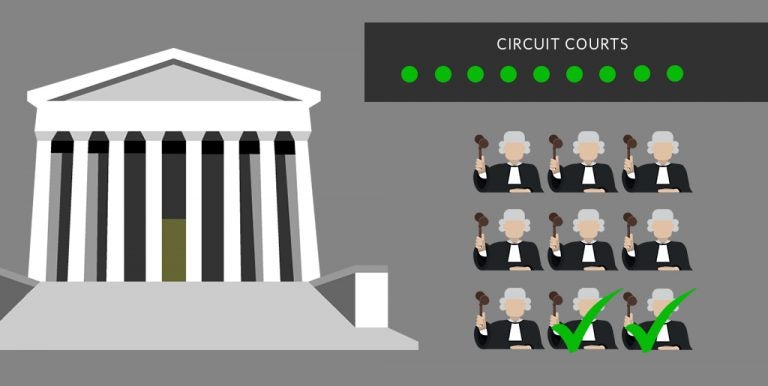

Two justices were added to the Supreme Court, bringing the total number up to nine. Democratic President Andrew Jackson signed this legislation on his last day in office. This last-minute legislation added two more circuit courts, which provided the justification for nine justices. For years, politicians had advocated the creation of new circuit courts to represent the new states. But since Supreme Court justices were still riding the circuit, it was clear that the creation of new circuits would mean the addition of new Supreme Court justices. President Jackson nominated the two new justices just as he left the White House.

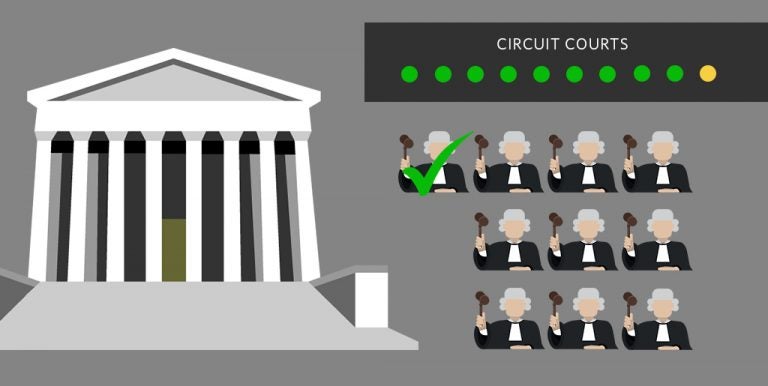

A tenth circuit court was added, giving Republicans the justification needed to add a tenth justice. Lincoln was motivated to add a tenth justice in response to the Dred Scott v. Sanford decision in 1857, which wrongly declared that rights and citizenship under the U.S. Constitution did not apply to Black Americans.

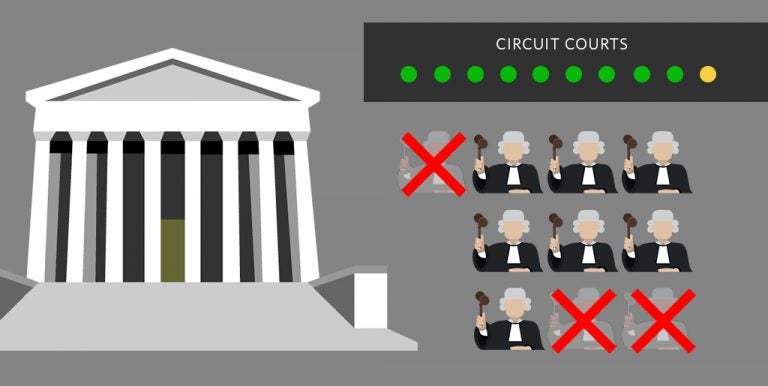

Congressional Republicans worried that Democratic President Andrew Johnson, who was sympathetic to Southern states following the Civil War and opposed to the Civil Rights Act of 1866, would exert his influence over the Court in order to reject Reconstruction. Republicans lowered the number of Supreme Court justices in hopes of limiting Johnson’s influence.

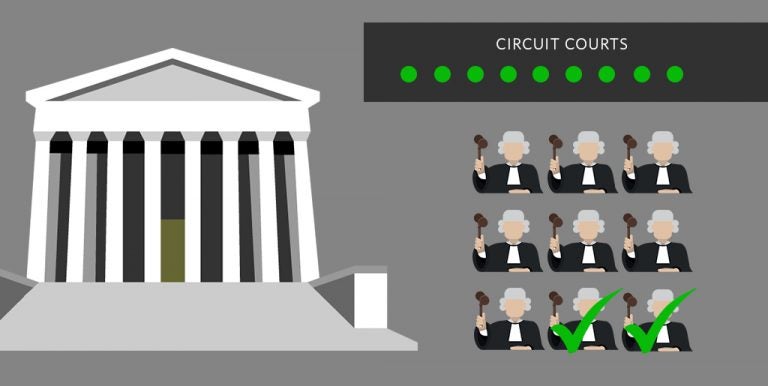

President Ulysses S. Grant authorized the addition of two Supreme Court justices, bringing the official total to nine, where it has stayed ever since.

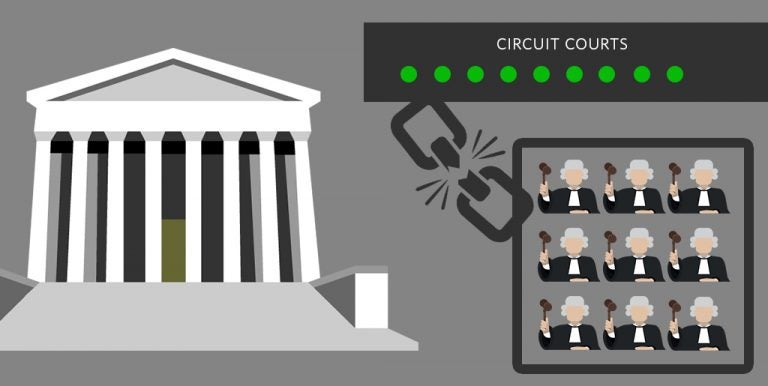

The custom of circuit riding ends, meaning that the number of Supreme Court justices no longer needs to correlate with the number of circuit courts.

Roosevelt disliked that the Supreme Court opposed some of the provisions of his progressive New Deal and tried to pack the court with more favorable justices. But the idea didn’t take. At the time, even his supporters saw it as an overt attempt to advance his own political agenda. The Senate Judiciary Committee called the proposal an “invasion of judicial power such as has never before been attempted in this country.” The Committee declared, “it is essential to the continuance of our constitutional democracy that the judiciary be completely independent of both the executive and legislative branches of the government.”

In response to the legitimate appointment of Supreme Court justices they don’t like, some progressives are openly advocating to pack the court with several new justices. For over 150 years—more than half of America’s history—the number of Supreme Court justices has remained stable. For decades, both political parties have viewed court packing as a radically partisan step that would exert undue congressional and executive influence on the judiciary and crush American freedoms—until now. Court packing advocates point to the events outlined on this timeline to make court packing seem routine. But history’s few partisan attempts to change the composition of the Supreme Court offer no justification for packing the Court today.

Leading Democrats are saying their party would be “virtually certain” to pass a Supreme Court “reform” bill if they win the presidency and both houses of Congress. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer recently said that bypassing the legislative filibuster is an option for some pieces of high-profile legislation.

"*" indicates required fields